The Seldom Mentioned History of Jewish Settlements in South Jersey

The era of “New Immigration” in the 1880s saw an emergence of immigrants from places like Russia that until then hadn’t typically been places immigrants emerged from. Within Russia was a multitude of Jewish citizens who existed in strife with the rest. The facets of Russian Nationalism, Tsardom and the Orthodox Church constituted the majoritarian will under which Jews subsisted. Though it could be suggested that the prima facie majoritarian will was really reflective of authoritarianism, the rule of Tsar Alexander III ensconced in “reactionary nationalism in the name of Slavophile ideals” 1 A much more probable paradigm of populism would take shape during the February Revolution of 1917 and undermine (and shortly thereafter kill) the Romanov dynasty.

Jews, in an effort to escape the pogroms, forced ghettoization and lack of political franchise in Russia, were among the waves of immigrants in the 1880s. While many would come to reside in New York City, an overlooked amount came to New Jersey. Across the United States, Jewish settlers, contrary to stereotypes of Jews as merchants, shopkeepers and craftsmen that congregated at or near urban centers, instead became farmers. Farming colonies were formed in New Mexico, Kansas, Colorado, Iowa, Texas and Michigan, among other states. However, the farms in New Jersey survived the trials and tribulations that the farms in those other states did not. The colonies in the South and the West faced demise because they could not overcome “poor soil, the climate, malaria or some other disease, prairie fires, lack of water or wood or equipment, floods, crop failures, inadequate markets, high interest rates, [and] burdensome mortgages.” 2 The colony on Sicily Island 160 miles northeast of New Orleans and the successor colony in Arkansas could not be saved from “the typical disasters of the region; torrential rainstorms, malaria, yellow fever, floods, heat, and isolation.” 3

The farms in New Jersey mostly survived where the others perished, excelling in spite of the difficulties, primarily due to congregating toward the fertile crescent that is South Jersey. Or whatever shape South Jersey is. In actuality, South Jersey is, or was, not particularly fertile at all: “When the poor, wild soil did not yield what it could not yield, when willing hands failed to find work that would help fill the bread basket, and when the aid of charity had to be invoked; then there was but little sunshine to cheer the dismal gloom. And the colonists had reason to feel discouraged. Theirs was a thin, shifting soil, which ages ago had been sorted and resorted by the waves, and the ocean was chary about leaving it little besides the rounded grains of quartz which compose 98 percent of the soil. Long years of hopeless toil, theirs and their children’s, were before them, and after all that work honestly and conscientiously performed what would they have? Unlike the fertile plains of the northwest, or the Tchernosyem of southern Russia, these South Jersey soils call for the application of manures or of commercial fertilizers, and without them they yield scarcely anything.” 4 The farmers persisted and found local markets for their produce and milk which was in great demand. They sold their grape wine in large quantities to New York and Philadelphia, especially to supply the Passover trade; “it is claimed by competent judges that some of the port wine from the South Jersey colonies is superior to that from California.” 5

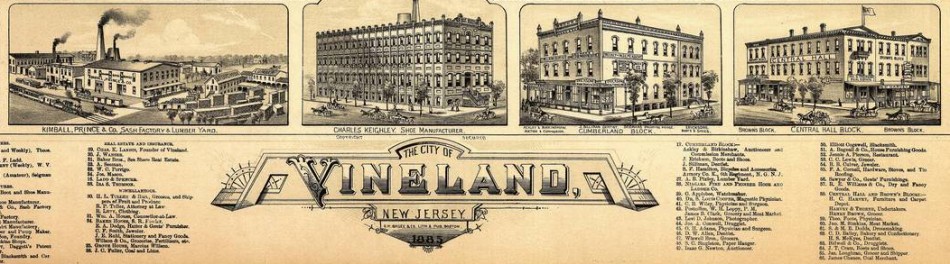

“Three towns marked the roughly triangular area in which the first New Jersey colonies were established: Vineland, Bridgeton, and Millville, all in Cumberland County.” 6 There is some synchronicity to the founding of Vineland by Charles K. Landis and the founding of these farming communities; Landis’ acquisition of property was largely motivated by a utopian vision and so too had these Jewish agrarian surveyors been motivated by utopianism. There was the Zionist sort of impulse in continuum with idealistic and ambitious colonization efforts. “While Americans saw in the Russian immigrants an opportunity to disprove ‘the oft-muttered calumny,” young intellectuals and idealists in Russia also wanted to prove to the world that ‘the Jew can live from the produce of mother earth.’ Although they had no experience in farming, they were committed to the idea of cooperative agricultural settlements. In 1881, they formed two groups: Bilu and Am Olam. Bilu prepared for immigration to Erez Israel, Am Olam for farming in America.” 7 Whereas the Bilu path is more inveterate in the Zionist imagination for being the impetus for the creation of the modern state of Israel, the Am Olam path sought providence not in the arid Palestine at which movement would be conditional upon the Ottoman residers, but in America. Influenced less by religion than by utopian ideas of emancipation and secular humanism and even at times socialism, the promise of prosperity through merit and enlightenment through labor emblemized by America was most alluring.

The farmers had versatile reasons for choosing their lifestyles. Some cited economic concerns, or religious concerns such as adherence to the Sabbath being easier in a rural rather than urban profession. “Some spoke of an ancient desire to own land of their own, so long denied most of them in the Pale of Settlement. Restless and rootless, the Jewish farmers looked for ‘a better, quiter life’ for themselves and their families. In a very real sense, the land, the farm, was a place which could nurture the fragile shoots of an uprooted family. To become rooted to one place in America was to become rooted to the whole of the new country, to make it a home.” 8

1. Brandes, Joseph, and Martin Douglas. Immigrants to Freedom; Jewish Communities in Rural New Jersey since 1882. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1971. 17. Print.

2. Brandes and Douglas. 49.

3. Brandes and Douglas. 47.

4. Bernheimer, Charles S., Ph.D. The Russian Jew in the United States: Studies of Social Conditions in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, with a Description of Rural Settlements. 1905. 376-388.

5. Bernheimer

6. Brandes and Douglas. 50.

7. Dubrovsky, Gertrude Wishnick. The Land Was Theirs: Jewish Farmers in the Garden State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 1992. 11. Print.

8. Dubrovsky. 47.